In episode 3 we visit Niagara Falls and ride all over the place in our trusty time machine

Checkpoint Charlie

now that we know what “Once upon a time” stands for — namely, as a kind of literary Checkpoint Charlie, reminding us that we’re about to enter a territory that’s foreign to our logical, empirical minds, and where the language that’s spoken is all metaphor — it’s time for us to cross that border and enter our woodcutter’s fairytale forest...

so, once again, here’s the first line of the manuscript, in English:

Once upon a time there was a poor woodcutter who lived before a great forest.

Beware of lumberjack conventions

As simple and generically medieval as this sounds, (I mean, calling this guy a lumberjack would totally change our mental image of him and his forest, don’t you think?) we could ask if this is supposed to be some sort of accurate historical fiction? and I guess it could be. at this point of the story, who knows...? except, that’s a logical question...

remember, we’re here to treat the fairytale as if it were a dream, so we’re going to treat each of the details as individual metaphor... and that means we’ll need our intuition to do the interpreting...

that said, it would be something of a no-brainer to talk about how a forest could and actually does stand as a metaphor for the Unconscious... that murky, mystery-medium our Consciousness swims in and that we only catch glimpses of in momentary flashes of Jungian or Freudian insight... not to mention our dreams...

there’s no need to belabor the point or spend any time dwelling on such an old psychological chestnut...

It’s such a well known symbol it might as well be considered a cliché, and therefore qualifies as a convention we can all agree on.

Except, just as we saw with “Once upon a time,” beware the cliché, and be particularly suspicious of convention.

Together they're a sure sign that we’re probably overlooking something of great value, something necessary for getting at the Truth in the fairytale... in other words, one of its lost jewels...

Resonance

Now before I get US lost and miss this forest because I'm so busy examining the trees, let me say that I was so impressed by an oral reading of just these first few words in German they actually held me spellbound...

you see, those simple words, told in a way that resonated so deeply, were enough to shake off cobwebs of convention that I hadn't even been aware I'd been lost in.

Of course, I'm hoping that my work here will do the same for you — not just with Hansel and Gretel, but with fairy tales in general — so you really need to hear that first line the way I did...

unfortunately, my German is schrecklich... so I have a special treat...

I was able to persuade that same storyteller extraordinaire, Jürgen Lexow, to record the complete fairytale for us... and as he so generously agreed, I’ll be sharing that complete recording with you... for now though, here’s that first line

🎶 Es war einmal ein armer Holzhacker, der wohnte vor einem großen Wald. 🎶

Humility before Majesty

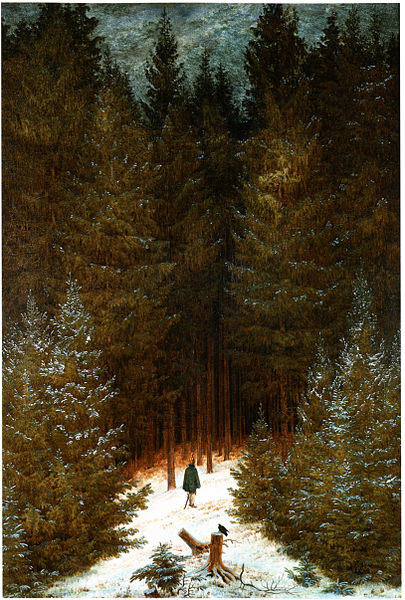

You see, because of the subjective power of Jürgen’s voice and the magical way he breathes life into the tale, I was able to picture in my mind a fairy tale forest of not just mysterious depth and enormous breadth, I saw its immense and majestic height, especially in relation to our poor woodcutter...

and the magical Gestalt of that image immediately transformed his poverty from the near-destitution of conventional thinking into the emotional / intuitive richness of simple humility.

And so this first line of the fairytale becomes an image of quiet pathos, with a typically humble peasant, not just living in the impressive and primal bosom of Nature, we get to see him as if he were alone, reverently kneeling in the solemn quiet of some great gothic cathedral.

Winterlandschaft - Caspar David Friedrich

Now, factually, our woodcutter may even be a pauper, yet if we don't allow for the paradoxical richness of his humility, we'll find ourselves missing out on the experience of something significant that might otherwise be left completely forgotten and under-valued — not just within the fairytale... within ourselves — namely: our own personal humility...

Unicorns

So look at what just happened: this first line — these first few words — quietly opened up to become a virtual tapestry of images...

and we’re going to observe this happening over and over...with each of its 42 sentences...

and that means this entire fairytale is the conceptual equivalent of those famous unicorn tapestries — the ones in NY,

— each with their rich medieval imagery, and their own suggestive, enigmatic symbolism...

The Unicorn is Found

now here, woven into this first line — as well as throughout the entire text — is a prompt to recall not just a deep and abiding spiritual characteristic of Nature, in other words, Nature as a sacred space / even a virtual, metaphoric cathedral / but the kind of people who felt this way about being in Nature... and especially, the forest...

Der Chasseur im Walde - Caspar David Friedrich

Roman eyes

and that takes us to a time long before the Middle Ages — and a factual report about a very particular place and a very particular group of people who were, in all likelihood, our woodcutter’s ancestors...

the year was about 98 CE and here’s a quote from that report:

Ceterum, nec cohibere parietibus deos, neque in ullam humani oris...

okay... sorry... that was the original language of the people being reported to...

here’s an approximate translation for us:

...they consider it unworthy of the grandeur of celestial beings to confine their deities within walls... or even to put a human face on them... Woods and groves are their temples, and they affix names of deities to that secret power which can only be seen by the eye of reverence...

In other words, this report is about people who considered the forest to be a holy place — a temple without walls — whose deities were metaphorically seen as a kind of disembodied power that could only be appreciated by means of a particular attitude or state of mind that our reporter called reverentia...

his exact words were: “quod sola reverentia vident.” — a phrase that english translators usually turn into a metaphoric eyeball... and which we can easily understand to mean an attitude of sincerity and humility...

our reporter was the famous Roman historian Tacitus...

and the full text of his report was called the Germania...

Writing nearly 2 millennia later, (in 1835) our own Jacob Grimm, echoed and affirmed this observation in his 3 volume work known as Teutonic Mythology...

waxing poetic in the chapter on temples he said:

In the sweep and under the shade of primeval forests, the soul of man found itself filled with the nearness of sovereign deities.

he also said something to the effect that: from the first, forest life had a mighty influence on the whole being of our nation...

The Intuitive Time Machine

and just like that intuition took us all the way back from our woodcutter’s medieval forest to the first written reports about those "rough barbarians living in the forests north of the Alps, and east of the Rhine..."

and then like a time machine it skipped ahead 1700 years and brought us right to what Jacob Grimm had to say about Germans and their earliest modes of worship...

and what these quotes do is give us the distinct impression that our fairytale wants to tell us something about Germany and Germans...

you see, this is the way intuition works with fairytales: it sends our logical mind off to the library in search of facts that might support whatever it's sussing out in between the lines... and those library facts give the tapestry of each sentence greater depth by adding more interesting and relevant detail...

in fact, one source usually leads to another which leads to another...

in other words, one good source will alert us to factual information we were unaware of, giving us more background information about the fairytale than we could have otherwise known...

what’s key here, is that the fairytale lovers of the Grimms’ Zeitgeist would have already been well aware of these facts...

in any case, this is the method we’ll be using to deepen the historical context of our fairytale as we patiently wait for the fairytale’s meaning and truth to make itself known to us...

Skeptical...?

of course finding historical sources and quotes that confirm what our intuition is telling us could be considered a logical fallacy: what’s known as confirmation bias...

except, we’re not fools...

like any good researcher — whether in science or the humanities — if we find facts and reliable sources that contradict or disprove our intuitive postulates we accept them gratefully... and re-adjust our theory...

after all, we’re only interested in the Truth... not in any pet theories...

most often what we find not only reinforces what our intuition was on to, it broadens and enriches the scope of Truth within the tale that we only had the most basic conception of...

that said, we now know that our intuitive sense was on the money, and that it wasn’t just our imagination telling us there was something metaphorically rich hiding in this first simple sentence... namely: the concepts of humility, reverence and sincerity...

Got Religion...?

taking that another step further, we can also posit that the rest of our tale is going to have something to do with religion...

and that might seem like a pretty big leap, coming as it does in just the first line of the story...

so we have to ask ourselves: are we jumping to conclusions by bringing up religion...?

it’s true that the Grimms essentially baptized the tale, by mentioning God at a number of points in every one of their revisions...

after all, they were solid citizens of their Zeitgeist, so tossing in a dash of religion seems a perfectly logical expression of both their personal character and their editorial intentions...

not so surprisingly though — just as the words "Hansel" and "Gretel" appear nowhere in our manuscript version, neither does the word “God,” and as far as religion goes, there’s no mention of prayer, praying or worship of any sort...

so, on whose authority or at least on what grounds am I bringing religion into the meaning of the manuscript...?

well... first there’s my intuition telling me this...

second there was Jürgen’s voice creating a picture of the forest as if it were a cathedral, and leading me to both Tacitus and Jacob Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology...

third, a surprising key to all this was the use of that word, "vor, “ in the text... Vor meaning in front of / or before... as opposed to "neben,” which would mean next to or beside," and which is closer to how many English translations of the story begin.

the most common one, Margaret Hunt’s translation of Hansel and Gretel, begins like this:

Hard by a great forest dwelt a poor wood-cutter with his wife and his two children.

“hard by” is something of an old-fashioned adverb or preposition meaning close by or very near...

which is all well and good for adding a medieval flavor to the story...

it just never gave me the jolt that the word “vor” did when I heard Jürgen for the first time...

maybe this sounds nerdy and over-enthusiastic, so let me explain what that word “vor” brought to mind.

The Numinous

I’ve visited plenty of Catholic churches and cathedrals in my life, (most often in Italy), but it was my very first experience of standing in front of (i.e. "vor") Cologne’s famous gothic cathedral that gave me an understanding of exactly HOW powerful of a physical metaphor a church building can be...

of course it’s iconic shape can be seen for miles and from almost any place in the city...

and arriving in its neighborhood from any direction, there’s no denying its imposing presence...

in a certain afternoon light though, what you can see in its impressively massive and impossibly tall western facade* — that is to say right in front of it — is nothing short of numinous...

Meaning, it can almost give you chills, because that combination of light and architecture actually makes you feel the presence of what’s commonly thought of as God...

*(actually, a gothic cathedral doesn't, technically, have a facade... expect to hear more about that picky, yet valuable, little architectural detail later on in the story)

the word itself (numinous) is not as important as the experience...

however, since the experience is something that’s woven into the tapestry of our story, I’ll probably be using that word more often, so let me just give you a brief explanation:

In his book, The Sacred and the Profane, Mircea Eliade, the 20th century Romanian historian of religion, calls what I experienced, and what those people that Tacitus was reporting on, a theophany (if you prefer the word God), or a hierophany, (if you’d prefer — as I do — something a little more open ended...)

these words actually mean the same thing as an epiphany (in its more original, religious usage)...

we can just call it a religious experience, although that still doesn’t tie it down to any particular religion...

in fact, the people of Jacob Grimm’s zeitgeist, many of them Lutherans, or, like the Grimms themselves, Calvinists, well, they would have called it the Sublime...

the word numinous was only coined in the 20th century...

Niagara Falls

over the centuries, plenty has been written about the sublime, but really, it’s all talk, not to mention, very tedious reading...

more to the point, if you’ve ever taken one of those famous "Maid of the Mist" boat rides to the foot of Niagara Falls, you know exactly what the sublime is...

standing in that boat not 50 yards in front of that impossibly powerful wall of water — the visual and emotional effect is uncannily similar to standing in front of the Cologne Cathedral...

It was only after hearing Jürgen read this fairy tale beginning, that I put 2 and 2 and 2 together... that is, I connected my memory of seeing the light on the Cathedral, AND my experience of Niagara Falls, with the mental image of our woodcutters Humility before the Majesty of the Great Forest...

and that gave me an understanding of exactly what ANY church building is meant to symbolize:

Cathedrals especially, (which are meant to be more inclusively collective than modest little parish churches) — from the dark depths of their deepest and creepiest romanesque crypts to the soaring tips of their tallest gothic spires — are meant to serve as physical metaphors of the very same Great Forest in this fairy tale... that is to say everything that our metaphor of the Forest implies... including the sublime, the numinous AND yes, even the Unconscious itself...

and that’s because they’re meant to elicit that very same, sublime or numinous experience of Majesty, Mystery and the Sacred in anyone humble enough to adopt our woodcutter’s attitude of reverence...

and just as an aside, it finally became more than obvious to me that the great cathedral at Cologne was built in such a way as to actually resemble a forest! doh...!

Crockets on the Cologne Cathedral

entering it, we’re meant to find (and find ourselves standing before) Majesty, Mystery, and the exquisite possibility of Salvation (which is, of course, is the Christian version of happily ever after) — something that in reality should make Christians so weak in the knees as to spontaneously fall to them.

Wotan & Co.

Now, as reported by Tacitus: long before the spread of Christianity, there was no lack of religious feeling in our woodcutter’s ancestors...

they simply had religion in their bones (as does everyone)...

although unlike the Romans, who enjoyed constructing marble temples to house their gods, these less sophisticated people had free-range gods...

and they had their experience of the numinous, al fresco, out in Nature, which for them, was mostly forest... (just as the plains and prairies were Nature for many Native Americans...)

so does that mean the religion in this story is going to be the German equivalent of Norse Mythology...?

well, on this point, it’s too early to say, since we’re always going to need more context to figure out things like this...

and whenever we need context, it’s off to the library...

okay, wikipedia...

which, btw, is actually a terrific resource for getting us started on the trail of factual discoveries...

what I mean is that no matter how well written and researched any given wiki article might be, it’s always only a stepping off point...

wikipedia gives us useful facts and points us toward relevant sources...

it’s always up to us to seek out those sources and find out for ourselves how relevant they actually are...

it’s also highly entertaining to see for ourselves just how biased or not those sources might be...and exactly what they have to say for themselves, without the skew of the wiki middlemen...

here’s a small example that gives us more background information about our woodcutter and his forest, while introducing another thread of religious influence that’s woven all through this story:

Willibald & Winifred

this time, the intuition time machine brings us to the 8th Century CE where we discover yet another report on the forest worship of the Germans...

and yes, this, too, was written in Latin... although, instead of a Roman, our reporter was a Brit by the name of Willibald...

and his report can be found in his biography of a certain Winifred...

over the centuries, what Willibald wrote was borrowed and paraphrased by numerous authors...

and his obvious bias was enthusiastically shared by all of them...

and while there was no exact English translation published before 1916, here’s a slightly embellished Victorian version published around 1873 that not only gives us more insight into the Zeitgeist of the Grimms, it puts a brand new wrinkle into the tapestry of this first line...

(He) found but few of his Hessian (converts) adhering to pure Christianity. They had made a wild mixture of the two creeds; they still worshipped their sacred groves and fountains; consulted wizards, and shunned weir-wolves. (So he) determined to strike a blow at the heart of the obstinate paganism. There was an old and venerable oak at Fritzlar, near Geismar, hallowed for ages to Thorr the Thunderer. Attended by all his clergy, (he) went publicly forth to fell this tree. The pagans assembled in multitudes to behold this trial of strength between their ancient gods and the God of the stranger. They awaited the issue in profound silence. Some, no doubt, expected the Thunder God to hurl his bolt and strike dead the Christian prelate. (He) swung the axe, and dealt several blows to the sacred tree. Then was heard a rushing sound in the tree-tops.... a few more vigorous blows, and the great tree cracked and came toppling down with its own weight, and split into four huge pieces, leaving a great patch of light in the green leafy vault, through which the sun fell on the triumphant Christian prelate. The shuddering pagans at once bowed before the superior might of Christianity. (He) built out of the wood a chapel to S. Peter.

so not only was our reporter a Brit, the guy with the axe was also a Brit whose name was Winifred, but who is actually better known as Saint Boniface — the patron saint of Germany...

and the tree he cut down, known as Donar’s Oak, is so famous it has its own Wikipedia page...

A Question of Paternity

well, that’s our introduction to this forest, to our woodcutter’s humility in the face of its sublime majesty and mystery, and to the not-so-subtle threads of religion woven into the tapestry of our fairytale...

in the next episode we’re going to get deeper into the story, and the mystery...

before we do though, we’ve just got to ask ourselves one question: who really is our woodcutter’s true ancestor...???

one of those reverential Germans Tacitus spoke of who eventually converted to Christianity...?

or could it be the Brit, Saint Boniface, arguably the most famous axe-wielder and woodcutter of all time, whose most famous act was to cut down the most famous tree that ever grew in Germania...?

well, we’re not out of the woods yet, so it’s something to think about...

Financials

next time, we’ll gonna dig a little deeper into our woodcutter’s financials as well as scrutinize his employment record and career choices...

and while that might sound utterly snooze-worthy, I guarantee there are some valuable jewels and entertaining Easter eggs hiding in the cracks between those straight looking, buttoned down lines...

in the meantime, visit the website for transcripts and links...

that’s betweenthelines.xyz...

and don't forget kristo's astrology and kristo.art

I hope to see you there...

alrighty then...

ciao a tutti...

vocal reading of Hänsel und Gretel / das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen (in German) by Jürgen Lexow

Music credits:

Beethoven - Sonata No. 21, Op. 53 in C Major Waldstein - I. Allegro Con Brio - performed by Paul Pitman and courtesy of musopen.org

Episode 2 - Once Upon a Time / Episode 4 - Financials and Career Choices